Pandora unboxed

Hope is making a memory box.

It is hard work, now that she is dead.

She died in the sixth month of the sixth year of their marriage. She died in childbirth. The child, too, died in childbirth. In a more literal sense.

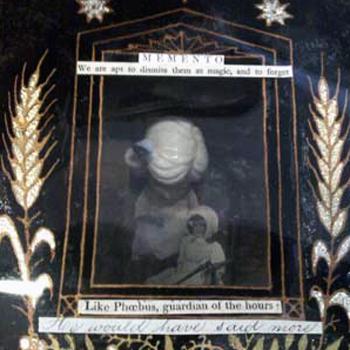

Hope puts the photograph at the bottom of the box. She likes to pretend that the little girl in the picture is her mother; perhaps her grandmother; perhaps even her great-grandmother. She likes to pretend there are stories about the doll that sits by the girl’s feet. A boon companion become a beloved heirloom.

But there are no stories, because the picture is of an utter stranger. Hope found it pressed between the leaves of a volume of Jonathan Swift’s poems, a volume she found in the abandoned house when they arrived. She has never even met the people who owned the house before them, has no idea if the girl in the picture shares a history with them.

But Hope has no stories of her own mother, or grandmother, or great-grandmother. All the mothers of her line died before she was born. That’s a tradition in itself, she supposes; she, too, died before her daughter could be born. But it is not one that she wishes to commemorate. So the picture will have to do, its imagined stories standing in for her own.

Once she would have rebelled at this pretence, proud of her foundling nature. But now she has grown used to having others tell her stories for her. She supposes that is what happens when you are dead, when you can no longer tell your stories for yourself. They talk, to her face, of how brave she was, how blameless. They talk, when they think she cannot hear, of how she has grown distant, and quiet, and strange.

And he, her husband; once, he told tall tales about her prodigious gifts; about her bountiful offerings of love, of sex, of company. Now, he only lists the evils that she has set upon him. He talks of imagined slights, of imaginary infidelities. The only story he does not tell is the truth. That story is not fit to be aired.

Angered, briefly, and surprised that she can still feel anger, she scribbles bitter words. Then, the flash of fury over, she reconsiders. On a fresh sheet of paper, she writes brief words of chastisement. She writes them in her best script, so that he will know that she they were well considered, not hastily wrought. She cuts them out, affixes them carefully to the lid of the box.

The box’s lid is lacquered, inlaid with pearlescent ears of wheat. Wheat for Demeter. Demeter, goddess of fertility. In marriage, as well as in the fields. Certainly Hope has not won Demeter’s favour. If she had, things would have been different. Perhaps then there would have been fewer breaches of marital contract, fewer stains on their sheets.

But perhaps the goddess will show mercy to her yet. After all, Demeter had a daughter who languished in the kingdom of the dead. Perhaps she will listen kindly to the sympathetic magic of the photograph of the pretend-mother. Perhaps she will return Hope to life. Perhaps once Hope has made the box, sealed it, offered it to Demeter, she will awake the next morning and arise again – like Apollo, like the sun – and turn to the day’s new work.

But Hope knows it is not to be. She slides the lid of the box open again, puts in the doll’s head. Its cool whiteness is smooth below her fingertips, and for a moment she closes her eyes and feels its weight, reluctant to let it go. She does not remember where the head came from; only that she has owned it since she was very young.

She remembers admiring the frozen set of its perfect hair; the pale blue bow peeking out at one side. It seemed so sophisticated, so adult. This, she thought, was what it was to be an adult, a woman. A perfect, immaculate, flawless figure.

Now she opens her eyes and looks at it again, and she realises it is nothing of the sort. It is a child’s head, and it has the perfection that only a child’s face – pure, uncontaminated by life’s harsh truths – can display. The eternal perfection of a child who will never grow old. She places it carefully, gently in the box. There, it can rest, undisturbed, forever.

One more item. This one she picks up without looking, drops it hastily in corner of the box. The instruments of her repair, still and eternally incomplete: it picks and scratches and itches at her every day. Her hand drops, almost without her knowing it, to where the ragged scar runs across her abdomen: the scar that saved her life, and caused her death, all in one and the same instant. The unholy wound through which her daughter was born, and died, in the moment of her first and last breath.

Hope’s eyes film over with tears and her breath grows ragged. Her stuttering fingers push back the lid of the box. The memories, sealed within, grow still and fixed.

But Hope, outside, finds no release.

How can it hurt so much when you are already dead? ##

Inspired by The Cotard Delusion, an artwork made by Amanda Schiff and exhibited at the Grant Museum of Zoology, London from February 15th- June 11th 2010

Yeah. It’s been a while.

A few months ago I heard that the Grant Museum – the tiny, deeply fabulous zoological wunderkammer embedded deep in the throbbing heart of UCL’s Bloomsbury campus – was running a short story competition. The Grant is a delightful place, packed – and I do mean packed – with its curiosities. A three-legged quagga! Glass slugs! A walrus’ penis bone! A jar of moles! And that’s not even the beginning of an introduction to it.

The focus of the competition was none of these wonders, but rather an art installation by Amanda Schiff. Pandora’s Box: Curiosity and the Dangerous Pursuit of Knowledge comprised a succession of boxes containing evocative found objects; the competition was for the best story inspired by the artwork – a challenge I found irresistible. (Mind you, Monkeys will know that I find pretty much any challenge irresistible.)

But then I went off on an unexpectedly hectic holiday to the Hay Festival. Educating myself at author talks, rummaging around in cavernous bookshops and repressing bilious outbursts at the middlebrow excesses of my fellow attendees left me with little time to write anything. Upon my return, there was the usual house remediation to take care of – and so by the time I sat down to write it was 10pm on Sunday 6 June.

Entries, the rules said sternly, had to be in by the end of the day.

Oh well. Just made it that bit more exciting. Thirty minutes of research and one hour twenty-five minutes of frantic typing later, I had produced Memories of Hope. Despite the haste with which I’d thrown it together, I was – and still am pretty pleased with the result. It’s not the most original of premises, but I flatter myself that the end result is quite thematically complex and genuinely derivative of the particular artwork I’d chosen. (More on that in the notes to the story, for those who care.) Not so much of the Grant Museum, however, which was a bit of a #fail on my part; after all, it was the setting that had attracted me to the competition in the first place.

Nonetheless, a few weeks later I got an email telling me that I’d won. Which is obviously very gratifying, though I do feel as though I should have worked a bit harder for it. (Those who’ve followed my fitful career as a writer of fiction may remember that I have previous form for winning competitions with a hastily submitted and somewhat off-topic entry.) But hell, I wasn’t going to let that stop me from accepting the prize, which includes some book tokens and publication on the museum’s website.

The best bit, however, is that I’m now an honorary Friend of the Museum – or rather, I will be once it re-opens, since it’s currently moving to new, less cramped premises. I’m quietly hoping they’re not too spacious; the density of exhibits was a large part of the Grant’s charm. But then, I don’t have to look after it; I suspect that it will end up in more modern surroundings that will both show off the collection to better advantage and allow the curators to take much better care of it. I’m sure it’ll still be be brilliant either way. Go visit when it reopens.

One thing you won’t see, though, is Pandora’s Box, which doesn’t seem to have been publicly documented anywhere, either. So it will have to live on – aptly enough – in the memories of those who saw it. ##

This story was written for, and won, the Grant Museum of Zoology’s 2010 short story competition. As mentioned in above, I had to come up with and write this story in less than two hours. A couple of people have asked how I did it, so here’s what I did.

I started out by reversing the premise of the original myth, in which a woman called Pandora opens a box containing hope. Perhaps, I thought, this should be about Pandora putting hope into a box – at which point it occurred to me that Hope is also a woman’s name. But who actually was Pandora? A bit of research (okay, fine, some frenzied cribbing from Wikipedia) revealed her to be a more ambiguous figure than I had appreciated.

The version of the Pandora myth that most of us recognise today – a meddlesome girl releases a flock of demonic ills to plague humanity — is due to Hesiod, and seems to be a misogynist revision of an earlier tale in which Pandora is a mother-goddess figure, rather than a foolish mortal girl. (The myth’s evolution and symbolism is actually pretty convoluted: see here if you’re interested.) I wanted my protagonist’s history to be shaped by that of her mythic archetype, and I decided to make her fertility the crux of her story.

So that the character and the action. But I didn’t have the theme yet. That came from the title of the particular piece I had chosen. was called The Cotard Delusion – pictured in a terrible camphone-through-glass picture above. What’s that? Here’s Wikipedia again:

The Cotard delusion or Cotard’s syndrome or Walking Corpse Syndrome, also known as nihilistic or negation delusion, is a rare neuropsychiatric disorder in which people hold a delusional belief that they are dead (either figuratively or literally), do not exist, are putrefying, or have lost their blood or internal organs. Rarely, it can include delusions of immortality.

The relevance is presumably obvious. (If not, I really have #failed.) Character, action, theme: go. The rest came naturally from the ingredients of the box…